Campaigning During COVID

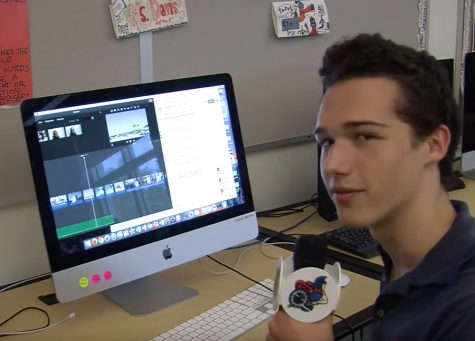

Photograph by AW

Andrew Weaver went door to door this summer as a campaign field worker.

After a grueling 18 months of campaigning, Commissioner Daniella Levine Cava clinched a second-place finish in the Aug. 18 Miami-Dade County mayoral primary, sending her to the November general election against fellow Commissioner Esteben “Steve” Bovo Jr. Despite a blitzkrieg of PAC smear campaigns and a pandemic that restricted her ability to reach voters, the commissioner squeezed out several other candidates to qualify for the runoff on Nov. 3. Her success came as a sigh of relief to many on her staff – myself included. I spent the summer as a field worker for the campaign, going door to door, mask on and socially distant.

After dedicating 10 weeks of my summer to Cava’s Neighborhoods Organizing to Win (NOW) program, a campaign wing composed of a dozen young volunteers from around the county, I was elated that all of our hard work had been worthwhile. Moreover, her strong finish was a vindication of the power of a grassroots political strategy, especially in a county where establishment-style politics has long gripped local elections.

But what secured Cava’s triumph as the lone progressive mayoral candidate? The answer is simple: her ground game.

The NOW program was instrumental in Cava’s ability to rise above the field of six candidates. Unlike her opponents who had reverted to all virtual and mail campaigns after the coronavirus pandemic struck, Cava was able to use young people like me to physically talk to voters and deliver yard signs across the county. As was told to me many times during the campaign, physical contact with voters is statistically proven to increase voter turnout and candidate favorability. This outreach proved to be crucial when almost all voters were at home practicing social distancing and paying closer attention to the local politicians managing safety protocols.

In my case, I was sent knocking on doors to all four corners of Northeast Dade – from Liberty City to Pine Tree Drive, the Upper East Side to Little River, and all people and places in between. In total, I knocked on some 1,800 doors, made 2,000-plus phone calls, and recruited 10 volunteers. But my personal numbers pale in comparison to the figures accomplished by the entire NOW program. Throughout the whole summer, NOW staffers reached upwards of 100,000 voters through canvassing, phone-banking, and yard sign delivery, making it one of the largest grassroots campaigns in Miami’s history.

No other campaign came close to the physical contacts Cava made, not even the presidential candidates. Former Vice President Joe Biden’s Miami-Dade County offices decided to halt in-person campaigning earlier in June, which brought their presence in South Florida to a worrisome low. However, Cava’s ingenious organizing strategies caught the Biden campaign’s eye for its Florida organizing playbooks. It may help secure Biden’s victory in a crucial battleground state that often decides who wins the Electoral College vote for President of the United States.

And in turn, Biden’s bid for the presidency as a Democrat could boost Cava’s quest to upset Bovo in the general election because Miami-Dade has more registered Democrats than Republicans. Bovo, seen as the front-runner, is a Republican and closely aligned with the conservative politics of President Donald Trump.

Without a doubt, Cava’s primary success can be partially attributed to the young canvassers who braved the pandemic conditions in hopes of attaining a more progressive county government they saw in her candidacy. The true victory, in this sense, was not her second-place finish on election night, nor the unprecedented primary voter turnout, but the fact that young people can make a difference when they have the means and will to fight for it. With much of Gen Z reaching voting age this year, nothing gives me greater hope for our future.

Andrew Weaver is a senior at MCDS and he is thrilled to serve as Campus News Editor this year. Since joining The Spartacus in his junior year, Weaver has...

Samuel E. Brown • Sep 11, 2020 at 8:02 am

Getting involved and communicating in-person with voters through canvassing and the phone is not easy work, but very rewarding when one makes a connection! Kudos on your and other students’ work to make a difference.

Christine Chancy • Sep 9, 2020 at 10:42 am

Great article Andrew! Young people like yourself can in fact make a difference. Keep up the great work! 🙂

Helen Kunde • Sep 7, 2020 at 11:40 pm

Thank you, Andrew, for your article and insight into how each one of us can engage in the political process to support our candidate of choice. Democracy works when we all get involved, and you have given us an example of a way to do that.